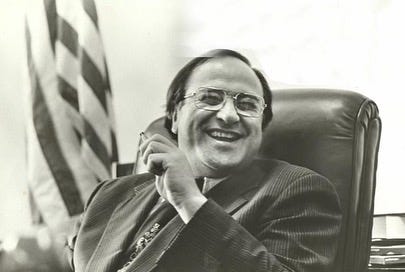

Jim Abourezk, brawler, maverick U.S. senator dies

Senator who stood up for Indians battled President Carter over Panama Canal

When he recounted his wartime experience as a sailor during the Korean War, Jim Abourezk would often joke that he spent the war fighting over women in Japanese bars.

Abourezk was born to brawl, whether it was in bars, courtrooms or on the floor of the U.S. Senate, where he represented South Dakota from 1973 to 1979 as the first Arab-American senator. A proud, in-your-face progressive liberal who championed Indians while attacking the privileged, Abourezk delighted in bludgeoning his enemies, of which he had many.

A man whose cussing would be considered copious even for a sailor, Abourezk had an insatiable appetite for good food, and, in an earlier period of life, good drink and cigars. He died Friday, on his 92nd birthday.

Abourezk’s time in elected office was short: His one term in the Senate was preceded by one term in the U.S. House. But his presence on the state’s political scene was felt for decades, and his brief stint in office jumpstarted the success of two younger Democrats, Tom Daschle and later Tim Johnson, who would each go on to successful and lasting House and Senate careers.

“My career would not have happened if it weren’t for Jim Abourezk,” said Daschle, who served on Abourezk’s Senate staff, a launching pad for his own 26-year congressional career.

“I think there are few people who had more impact on public policy in eight years than Jim Abourezk,” Daschle said.

Modest upbringing in Indian Country

James G. Abourezk was born in 1931 in Wood, South Dakota near the Rosebud Indian Reservation. His father, who had immigrated from Lebanon in 1898, opened a store in Wood in 1920. Growing up in Indian Country, Abourezk had a unique window into the impoverished, hardscrabble life of Sioux Indians. As a young man, he looked down on them, he admitted in his autobiography, but as an adult he would champion them.

After getting expelled his senior year for tying a teacher to a radiator, and then getting kicked out of his house by his parents, Abourezk moved in with his brother in Mission. He graduated from Mission High School and, at age 17 and with the permission of his parents, joined the Navy, which he hoped would open a world to women and adventure.

He completed basic training and then graduated as an electrician’s mate before being assigned duty in post-World War II Japan. A year later, in 1950, war broke out in Korea, and Abourezk assisted war efforts for allied troops. He took judo lessons, but much of his free time was spent chasing women and drinking beer. He stayed in Japan for three years.

“I had to ask for a transfer after three years,” he said in an interview. “I didn’t think my body could take it anymore.”

After leaving the Navy in 1952, he made a short attempt at ranching on land his father left when he died in 1951. But Abourezk couldn’t stand the isolation. He married his first wife, Mary, later that year, and the two started a family. Abourezk worked as a bartender in Wood, South Dakota and then Winner, where one of his chief skills was fighting unruly drunks. In Winner, a family doctor from the East Coast introduced him to The Nation, The New Republic and journalist I.F. Stone, which set the direction for his left-wing political ideology.

From Navy and bartending to engineering and law

In his mid-20s, with a wife and two children and uncertain career prospects, Abourezk enrolled in college at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. The family lived in a veterans’ housing apartment. By day he took classes. By night he would bartend, teach judo lessons and sell blood in order to earn money.

Work proved equally elusive after he earned his engineering degree in 1961, and in 1963 he enrolled at the University of South Dakota School of Law, fulfilling a dream to go into the law.

He established a law practice in Rapid City, and in 1968 ran unsuccessfully as the Democratic nominee for state attorney general. Although he lost, Abourezk proved to be a vigorous campaigner and debater. Following the election, rural electric cooperatives hired him to campaign against a bill championed by Gov. Frank Farrar. The bill, which narrowly passed in the Legislature, created a statewide commission to regulate gas and electric providers and was thought to give big energy providers advantages over rural co-ops. The bill was referred to voters, and Abourezk led the opposition, traveling the state making speeches against the new commission and Farrar.

The controversy ruined Farrar, who went on to lose re-election in 1970. The year proved pivotal for South Dakota Democrats. The state’s two longtime Republican congressmen, E.Y. Berry and Ben Reifel, both retired. Republican Sen. Karl Mundt, a political powerhouse, had been incapacitated by a stroke. Abourezk considered running for governor, but, to appease his wife, ran for South Dakota’s western congressional seat.

Political victory

He beat Republican Fred Brady, running against the Vietnam War and highlighting Brady’s call for mandatory citizenship camps for the nation’s youth, which Abourezk compared to Nazi Germany’s Hitler youth program. Election night in 1970 saw Abourezk and Democrat Frank Denholm capture the state’s two congressional seats while Democrat Dick Kneip beat Farrar.

With Mundt unable to run in 1972, Abourezk ran for the seat against Robert Hirsch, a Yankton lawyer and Republican majority leader in the state Senate. Abourezk’s victory on election night was tempered by Sen. George McGovern’s defeat to Richard Nixon in the presidential race. Abourezk and McGovern held a joint election-night party, but it was a somber evening when McGovern was unable to carry his home state and lost to Nixon in a landslide.

Shortly after being sworn into his Senate seat, Abourezk and McGovern traveled to Pine Ridge to negotiate with members of the American Indian Movement in an effort to end their standoff with federal agents at Wounded Knee.

Abourezk and McGovern would serve together for the next six years, Abourezk often in the shadow of McGovern, who was still considered a potential national candidate for president or vice president, while Abourezk was considered a maverick who would filibuster bills he didn’t like. The two reveled in their liberal political ideologies. They both visited Cuba and befriended Cuban President Fidel Castro, and in 1977, they took a team of basketball players from the University of South Dakota and South Dakota State University to play games against Cuba’s all-star team.

“He was a charmer – a very smart guy,” Abourezk said of Castro. The relationship, as well as later relationships with dictators in the Middle East, would open Abourezk to criticism that he coddled dictators and murderers.

Too liberal for critics

He was also criticized for favoring government regulation and higher taxes, which made him a target for the economic policies that were ascendant in the Republican Party and which would emerge dominant in the 1980 election of Ronald Reagan.

“The reason why American business is drowning in an ocean of governmental red tape is precisely because of busybodies like Sen. Abourezk, who spend their waking hours dreaming up solutions for which there are no problems,” wrote the conservative John Lofton in a 1976 column critical of Abourezk.

Abourezk cared little about what his critics said. He was strong willed, which put him at odds with his colleagues.

“At that time at least, a lot of compromise was done to get things done,” said Glenn Feldman, an Abourezk staffer. “Jim was not a good compromiser.”

He was also a frequent critic of Israel, which put him at odds with both Democrats and Republicans.

“They are mean bullies,” he said of Israel in 2015. “They are like the Islamic State except they know better than to behead people on camera.”

In the Senate, he filibustered a bill to deregulate the natural gas industry, and he killed a bill that would have given the airline industry billions of dollars to buy quieter aircraft.

But it was his work on behalf of the nation’s Native Americans where Abourezk cemented his legacy

“His legacy is still part of the Senate,” Daschle said. “We didn’t have an Indian Affairs Committee before Jim Abourezk.”

One of his most important pieces of legislation was the Indian Child Welfare Act, Feldman said. Prior to the act, Indian children were routinely removed from their homes and tribes, and they would lose contact with their culture. ICWA required child welfare agencies to place children who were removed from abusive homes with family members or within their tribes.

“He was well known in Indian Country as a guy who had spent eight years fighting very hard for Indian rights and sovereignty,” Feldman said.

It was clear that Abourezk did not like the Senate. On Jan. 24, 1977, he announced he would not seek a second term, citing his family, which he called his “TV answer.”

“My family is part of it, of course, but I can’t take any more of this stuff,” he said later that year.

“I resent that I don’t have time to think, maybe to write, to take photographs, to play my guitar. I need to make more money and retire some debts. I know I’m tired of marginal victories. And each time you run you have to peel off a principle here, a principle there. I’m not disillusioned, just realistic.”

On his final day in the Senate, he told reporters: “I can’t wait to get out of this chicken (expletive) outfit.”

He opened a law practice in Washington, divorced his first wife, remarried, divorced again and in 1991, married a third time to Sanaa Dieb, a Syrian woman who was attending school in Washington. He founded the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, and frequently defended the Palestinians and Arabs while attacking Israel.

Reveling in having enemies

In 1996, Abourezk saw an opportunity to attack one of his lifelong enemies: Larry Pressler, who had succeeded him in the Senate. Abourezk had always blamed Pressler for fueling the narrative that Abourezk had not run for a second Senate term because he feared Pressler. Now, Pressler was battling for his political life against Tim Johnson.

Abourezk booked a speaking tour for Alexander Cockburn, a liberal columnist, to discuss his new book, “Washington Babylon.” The book included a chapter on Pressler, which accused the Republican senator of being gay and a “dunderhead.” Pressler lost to Johnson a few weeks later.

Abourezk made frequent trips to the Middle East, taking friends with him. Tom Dempster, a former Republican state senator, went on one of the trips. Abourezk had many political contacts in the area, which included Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, and the former senator introduced his friends to those contacts.

Abourezk, Dempster said, was a “brilliant, alpha male, take-control guy.”

“Jim Abourezk was one of those guys who could get in the middle of a conflict and come out with a resolution,” Dempster said.

In more recent years, Abourezk could be found holding court at his wife’s restaurant, Sanaa’s. He remained critical of U.S. policy in the Middle East, and defended Assad from U.S. attacks even after Assad was accused of committing crimes against his own people. Abourezk said he doubted that Assad used chemical weapons on his own people, and he said the accusations were being used to stoke U.S. intervention in Syria’s civil war.

“He’s an absolute dictator,” he said of Assad. “But if you overthrow Assad, ISIS will take over the whole (expletive) country.”

In 2019, a scene from Abourezk’s 1989 memoir, “Advise and Dissent,” made the news. Abourezk had described a confrontation he had with Delaware Sen. Joe Biden. Abourezk, as chair of a Senate subcommittee, had blocked at the request of the NAACP an anti-busing bill that Biden sponsored. The scene became newsworthy 40 years later because Biden was seeking the Democratic nomination for president and had been criticized for working with segregationist senators.

“I (expletive) him up good,” Abourezk said of Biden.

We lost a great, great man today. I hope his life will help inspire young progressives in South Dakota to continue his legacy of advocacy and compassion!

I campaigned for Jim in 1968 believing he could make change for the good after the corruptions happening then in South Dakota and finally met him during the crazy and way too fun races of 1970. He was a practical joker and always held court wherever there was at least two people in the room. I will miss him and his idealism.